It seems like it would be impossible to make a film about a romance between musicians that would be utterly devoid of passion, but The History of Sound proves it can be done. For a film that wants you to believe that Lionel’s (Paul Mescal) relationship with David (Josh O’Connor) was the defining point of his life, it goes out of its way to not craft a sense of intimacy.

One could say that the relationship between Lionel and David is the film’s core, however, the two characters do not spend a meaningful amount of time together in the film to truly warrant that claim. At the beginning of the film we see Lionel meet David by singing with him at a bar, then move to a handful of dull conversations and images of an implied sexual encounter between the two. By the time these unconnected snapshots have ended, the pair is immediately broken up as David is drafted into WWI. The time between their meeting and separation is under fifteen minutes, and leaves no sense that Lionel has any deep feelings for David. There is little connection or character growth across scenes. which flattens vibrant moments into mere vignettes, sapping the story of cumulative effect.

The parts of the film where David and Lionel are not together are somehow even more dull than their short passionless encounters. While there is some beautiful imagery of the unforgiving Appalachian wilderness after Lionel moves back home upon finishing school, the film gives no reason us to understand why we are seeing these images or why we should care about their contents. It then falls into a stand-still, as Lionel aimlessly moves about his farm life, interacting with family and friends who are not given enough depth or dialogue to be considered relevant to the audience.

The film picks back up when David returns from war and invites Lionel to join him on a research trip collecting folk songs in rural communities. This is by far the best segment of the film. For a solid twenty minutes, the film is able to blend well-shot visuals of nature, a compelling score of American folk music. It also gets its closest to creating a romantic mood in this part of the film through direct visual allusions to other queer films. Lionel and David lying in the grass, whispering by the fire, and sleeping in a tent together, create images that are obvious replications of scenes from Maurice (1987), My Own Private Idaho (1991), and Brokeback Mountain (2005). These references fall flat as the film seems to misunderstand why the films it is referencing are so effective. All those films have been lauded for creating intimate, relatable relationships that offer both queer and straight viewers emotional access to their love and struggle. By contrast, there is still a striking lack of chemistry between David and Lionel. Their conversations are as empty and their sex scenes are sterile. The film’s choice to keep intimacy off-camera fails in letting the characters communicate genuine desire, belonging, or romantic development . So, when the two are separated again at the end of this chapter, it feels like nothing has really changed in the narrative.

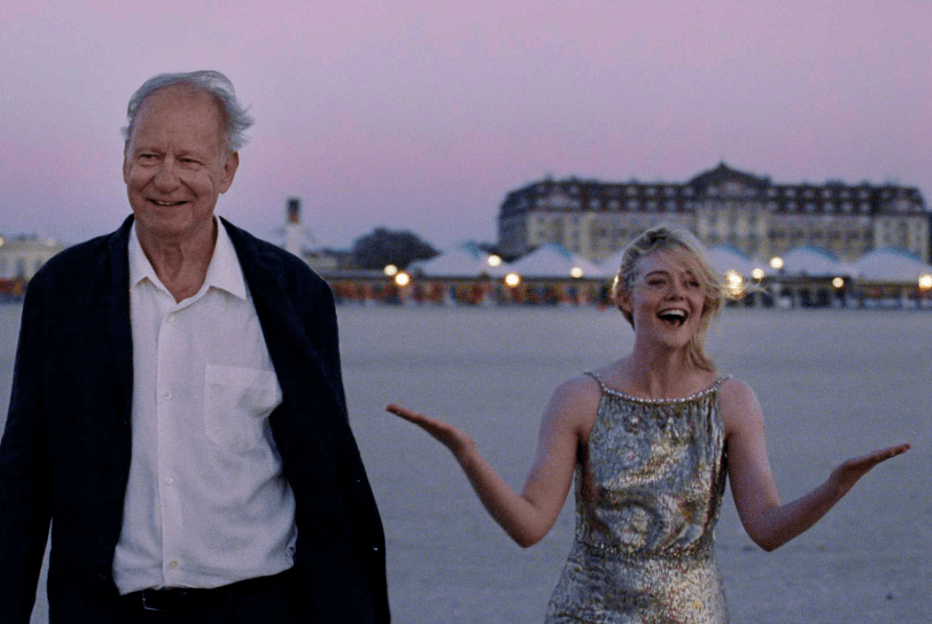

When the film is focusing solely on Lionel, it is almost painfully impersonal. He drifts between incredibly scenic European locations and reaches heights of successes in his career as a conductor, but to no real end. Similar to the rest of the film, the lack of drive keeps the picturesque technical work from feeling meaningful. It may delight the eye but leave hearts untouched. Lionel’s actions also do not construct a nuanced or endearing character to which the audience can relate. Over the course of the film, the lack of personality becomes increasingly frustrating, especially since the its structure as a character study. The film does not move or proke, making it ultimately forgettable despite its polish.

In its final third, the film attempts to foreground the its thematic elements. This is a film which is ostensibly about many things: being a queer in a homophobic society, trauma. grief, and the power of music. It certainly has the set up of a story that could be emotionally impactful, but it never synthesizes these elements into a coherent thematic throughline. The end result of this lack of real substance is a movie that constantly leaves you asking “So what?”, and never provides an answer, missing the chance to contribute to ongoing conversations about art’s ability to address loss, love and identity .

Mescal and O’Connor both give pretty decent performances, despite the stiff script they were given to work with. Even still, there is a distance created between the two in almost every scene of the small runtime they share together. It often feels like the script is asking them to talk at each other and not with each other, a massive detriment to a story that is supposed to be about their deep connection.

The History of Sound is a film which relies on viewers caring about the film’s characters and their relationship, however it is so stony that you might walk away wondering if the characters ever really loved each other? If you are looking for a film that explores queer identity, and hidden romance, your time is probably better spent on elsewhere.